Ouvidoria

Por que todos os lugares são iguais. A institucionalização do mercado imobiliário e a ascensão de lugares "sem lugar".

Descrição

Tradução do último parágrafo:

Consequências e o que deve ser feito. E daí? Quem se importa se o ambiente construído da América se torna institucionalizado? Todos os desenvolvedores são aproveitadores gananciosos que pouco se importam com o que constroem, certo? Errado. Antes do surgimento do zoneamento e da consolidação do desenvolvimento, o país era repleto de lugares especiais com uma arquitetura vernácula maravilhosa. Estas foram cidades e vilas construídas por muitas mãos. Cidades e vilas que envelheceram graciosamente por gerações de administradores, construindo iterativamente a partir das fundações de seus antecessores. Nova Orleans, aquela cidade tão querida, é um dos lugares mais excepcionalmente belos que se pode imaginar, com uma identidade tão única quanto misteriosa. Quando você está lá, você nunca pode se enganar por estar em qualquer outro lugar. O mesmo vale para Nova York e São Francisco. Santo Agostinho e São Paulo. Cada lugar é construído não só com materiais e design nativos de seu entorno, mas, mais importante, está imbuído das histórias de quem veio antes e deixou seus legados nas ruas que percorremos e nas fachadas que percorremos. São lugares de imensa significado cultural e história. Alguns reverenciados em escala global, outros felizes em manter a tradição em suas próprias comunidades sem um reconhecimento mais amplo.

Quando retiramos o contexto das comunidades e da história, profundas consequências se manifestam em sentimentos de falta de pertença. Onde não há nada para nos aterrar, não há conexão, o que nos despersonaliza de nosso entorno. Com a ascensão da internet e das mídias sociais e o declínio da identidade quando se volta para o mundo real, não é de se admirar que nossa sociedade tenha entrado em uma crise de solidão. Estamos sem leme.

Why Everywhere Looks The Same

The institutionalization of real estate and the rise of ‘placeless’ places

Coby Lefkowitz

Apr 28·13 min read

Many of America’s towns and cities could charitably be described as boring. New development, that is. America is home to an incredible diversity of regional architectural and planning styles. We cherish what makes each of these places special, traveling far and wide to take in their idiosyncrasies and beauty. But somewhere along the way, we stopped building according to local traditions. Over the last 70 years, America hasn’t put its best design foot forward.

It would be disappointing enough to fail in gracing a land as physically beautiful as the US with the built companions it deserves. But it’s downright shameful that we deprive ourselves of living in interesting, meaningful, and wonderful places, given the thousands of precedents for inspiration worldwide, and many hundreds within our borders.

Instead, we’ve copied and pasted our society from the most anodyne, the most boring, and the most bleh.

We’ve all seen them. Covered with fiber cement, stucco, and bricks or brick-like material. They’ve shown up all over the country, indifferent to their surroundings. Spreading like a non-native species. And no, I’m not talking about sprawling suburbs. They go by many names: Texas Doughnuts, Fast-Casual Architecture, McUrbanism, five-over-ones, those big bad boxes that stretch across the block. Spongebuild Squareparts.

What’s behind this bland sameness? While it’s been well explained before, I think only a fractional part of the story has been told — that it boils down to costs and codes. But this growing real estate trend extends beyond these two factors. As I see it, there are four reasons why our places are looking increasingly the same.

1. Constrained by codes: zoning and international building codes

Zoning is often the underlying explanation for the current state of American real estate, housing, and planning. Codes were developed in the 1920s and 1950s, and reflect the desires of planners and city makers of the time. Namely, a predominance of single-family detached homes with streets oriented around cars. As the mid-century progressed, zoning codes were quickly adopted around the country by planners eager to prove their town was modern and forward-thinking in its vision for the future.

As there are nearly 20,000 incorporated places in the US, with the vast majority of them home to fewer than 10,000 people, most towns didn’t (or don’t) have the time or the resources to develop their own codes. It was simply easier to copy what neighboring places did. And so, standard codes were transcribed from one municipality to the next. This is the origin of our places beginning to look the same, at least from an urban design perspective.

Though building codes have existed in some form for centuries, the modern set of regulations we use, the International Building Code, was developed in 1997. It was designed to serve as a model building code for jurisdictions around the US. That’s exactly what it became. Just as zoning codes were copied and pasted from one place to the next, towns and cities quickly adopted the IBC standard to guide the construction of new properties. The code is fairly prescriptive. It can be restrictive in the types of materials it allows for, the processes of development, and ultimately the final result.

IBC codes dictate building on a macro level. When a meaningful change is instituted that frees up suppressed demand, all it takes is for one pioneer to prove the viability of the concept for the industry to follow. In his Bloomberg piece, Justin Fox lays this out:

Los Angeles architect Tim Smith was sitting on a Hawaiian beach, reading through the latest building code, as one does, when he noticed that it classified wood treated with fire retardant as noncombustible. That made wood eligible, he realized, for a building category — originally known as “ordinary masonry construction” but long since amended to require only that outer walls be made entirely of noncombustible material — that allowed for five stories with sprinklers.

He continues:

“By putting five wood stories over a one-story concrete podium and covering more of the one-acre lot than a high-rise could fill, Smith figured out how to get the 100 apartments at 60 percent to 70 percent of the cost.”

Cheaper construction costs are great, but on their own, they’re not enough to explain the proliferation of five-over-ones we’ve seen. The story goes on.

2. Constrained land uses lead to more expense costs

Even in our largest cities today, much of the land is zoned for detached single-family homes. This leaves fewer plots of land available for apartment buildings, regardless of the underlying demand. Where demand outpaces supply, prices rise. It’s little wonder that in San Jose, a city of one million people where it’s illegal to build anything but single-family homes on 94% of the land, the average rent for studio apartments exceeded $3,000 a month pre-pandemic. This is indicative of a systemically broken regulatory system, with far too little land allocated to multifamily housing.

As a result of the lack of “legal” land to build on nationally, new multifamily buildings are usually limited to downtown cores, along busy roads, off of highways, or close to industrial uses. Apart from downtowns, a lot of this land is undesirable to live on or even reside nearby, for those with the means to choose. The most desirable sites are thus even further limited in a city or town. This serves to increase prices even higher. As an aside, these plots of land are also the most visible places we pass every day. And because most of us rarely veer off the main roads where these are built, we drive by the sameness over and over again, furthering the feeling of everywhere looking the same. Back to cost.

Stick-built five-over-ones, while more affordable than steel-or-metal-framed buildings, are still massive construction projects that require a lot of money, in addition to the upfront acquisition costs of the land. The more expensive land gets, the more units have to be built to yield a return for the developers.

3. More expensive land leads to a concentration of development by the few, most-well capitalized groups

Who gets to participate in the development process when land costs are so high? Only the most well-capitalized. In many places, it’s no longer possible for small developers, or would-be developers, to participate in markets. This is the fulfillment of a vicious cycle: land costs rise, which pushes out smaller developers, which leads to larger developers taking more market share, who in turn bid up land prices, which pushes out relatively smaller developers, and so on and so forth. The more prices rise, the fewer groups there are that have a hand in shaping our cities and towns. Our places become visions of the few.

These aren’t local groups. When projects reach a certain scale, the resources required to exceed the means of all but the wealthiest developers in a place, even in major cities. While the development industry isn’t as concentrated as the real estate private equity firms who have been buying up America’s homes, which are primarily headquartered in New York and other superstar cities, the external consolidation is still a real and pressing concern.

Like gasoline on a fire, an influx of institutional capital chasing high yields has fueled this consolidation of builders. This has provided an even greater advantage to large firms acquiring and developing sites over their smaller, less well-capitalized competitors. Concentration intensifies.

At the turn of the millennium, institutional investors allocated just 2–3% of their portfolios toward real estate. But two decades later, target allocations have jumped north of 10%, a ~3–5X increase. This spike tracks eerily close to both the increase in private construction spending since the mid-90s, and the balance of outstanding multifamily loans originated in the last 25 years, which have increased from $288 billion to $1.37 trillion. This trillion-plus number represents 40% of outstanding commercial mortgages, up from 22% in the mid-90s. How quickly the narrative has changed for multifamily developers. Just 30 years ago, apartments were an afterthought to institutional investors, who deemed them unworthy of sophisticated capital.

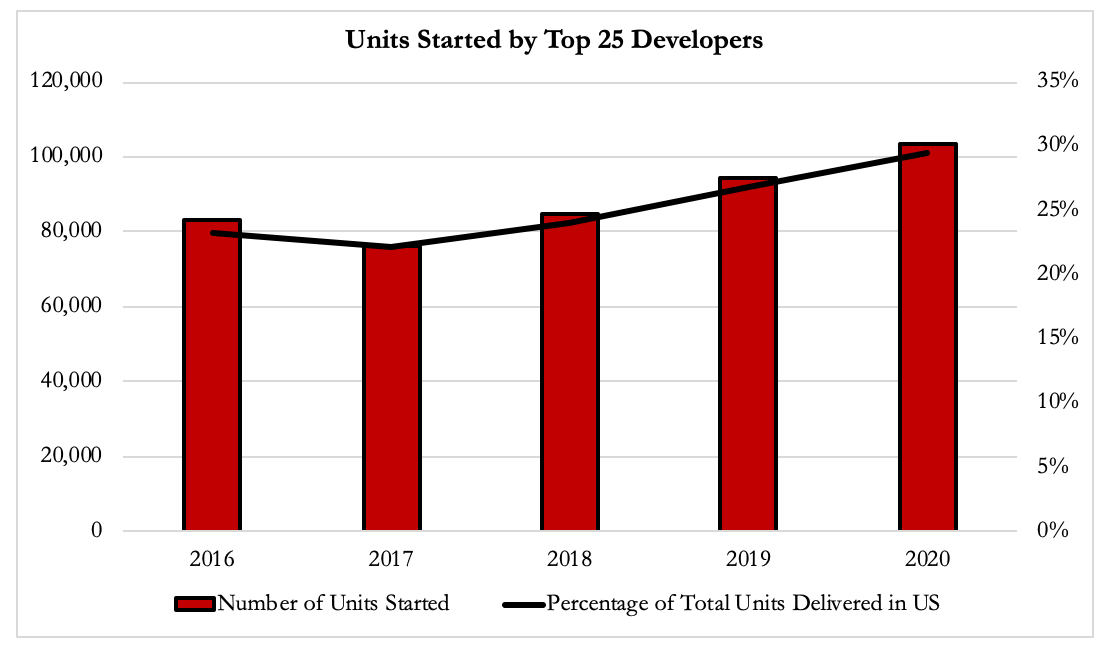

For a more tangible perspective on the state of sameness today, we can turn to the largest 25 developers in the country. From 2016 to 2020, these firms broke ground on ~442,000 units. Though we don’t have the data for completions in 2019 and 2020 yet, by trending completions from 2016 to 2018, we can project that 1.76 million units will have been completed from 2016 to 2020. In this 5-year period, the 25 largest developers will have produced a quarter of the supply of apartment buildings nationally (2 or more unit properties). These 25 developers are projected to deliver nearly 30% of the entire multifamily housing supply in America in 2020. This is a shockingly high number! The market is a near oligopoly.

4. Economies of scale

With the largest developers in the country delivering thousands of units a year for their institutional partners, there’s a need to economize where possible in order to hit their required returns.

The first step towards economization is to build as many units as possible on each lot. On the surface, this makes sense because zoning has so thoroughly constrained multifamily development that there’s a desperate need for more housing across the country. But this amount of housing isn’t inherently a good thing. It can be poorly located and is seldom designed well. It’s not because good design costs more. It doesn’t. It’s an excuse to hide behind a lack of care and creativity from spreadsheet developers, enabled by our regulations.

Not only do zoning codes mandate what can get built where, but they also dictate the form those buildings take. They regulate the mass, bulk, and setbacks of properties, among many other considerations. When mass, bulk and setbacks conspire to allow a full site build-out, the result is a rectangular box extruded up from the boundaries of a site. This is called building out to a site’s full envelope. It’s a tactic well-used in DC, where buildings are constrained by how high they can rise, so they rise out as much as possible. Queue the boxes.

After the maximum amount of units are penciled in, the next step for an institutional developer is value engineering. Value engineering is the process of stripping back the materials and design to the bare minimum needed to get a project built. This results in the cheap, and cheap-looking housing that so many identify this new era of development with.

Once a building is finished, replete with its boxy form, units jam-packed inside said box, and value-engineered materials, further economies of scale kick in. If the developer is happy with the architect, engineer, and leasing brokers from the project, they’ll simply copy and paste the team from one development to the next, regardless of the location. Remind you of zoning and building codes? The work required to form teams in each market is an intensive process of relationship building and ingratiating oneself to a new community. Out-of-town developers have no interest in doing such things.

This is why a project delivered in Tampa can look the same as one completed in Fargo. Despite the near opposite local contexts, it’s possible the same developer has recycled the same design to create the same building with the same team, leased to the same chain store retail tenants. Even the same vague and insufferable name like The Point can be recycled, by replacing at Tampa, with, at Fargo. Audaciously, institutional developers march forward, ignorant of what makes Portland, Maine different from Portland, Oregon, or Philadelphia from Kansas City. Unique local traditions? Completely different climates? Hah! Jokes on us. A box fits just as well in any of these places.

Everything looks the same because everything is the same!

This overall effect is exaggerated where developers acquire entire city blocks. These are banal and monotonous structures that offer little relief or stimulation to passersby. Despite how soul-crushing these may be, the scale of institutional capital necessitates the development of the largest sites possible, built out to their full extent. It doesn’t make sense for firms playing around with billions of dollars to spend time breaking up a site into several smaller, fine grained buildings. Not only is this because block long monoliths are their equivalent to smaller projects, but also because the thought and consideration put into well planned sites is beyond the scope of institutional development firms. The teams are oriented in such a way that building a 20, 30 or even 50 unit development is quite literally not worth their time. It’s just too small.

Indeed, as institutional capital allocations have flowed into real estate over the last decade, the number of apartment buildings with more than 50 units has grown exponentially. If I were a statistician, I’d say almost in correlation.

This has come at the expense of smaller units, and by extension smaller developers. What these charts represent is nothing short of the institutionalization and homogenization of American real estate. We have copied and pasted ourselves into a world where everything looks the same, and yet nothing is familiar.

Consequences and What’s To Be Done

So what? Who cares if America’s built environment becomes institutionalized? All developers are greedy profiteers who care little for what they build anyway, right?

Wrong.

Before the rise of zoning and consolidation of development, the country was full of special places with wonderful vernacular architecture. These were cities and towns built by many hands. Cities and towns that aged gracefully through generations of stewards iteratively building from the foundations of their predecessors. New Orleans, that much-loved city, is one of the most exceptionally beautiful places one can imagine, with an identity as unique as it is mystifying. When you’re there, you could never mistake yourself for being anywhere else. The same goes for New York and San Francisco. St. Augustine and St. Paul. Each place is built not only from the materials and design native to its surroundings but more importantly, is imbued with the stories of those who have come before and left their legacies on the streets we walk and facades we take in. These are places of immense cultural significance and history. Some revered on the global scale, others happy to carry on tradition within their own communities without broader recognition.

When we remove the context of communities and history, profound consequences manifest in feelings of a lack of belonging. Where there’s nothing to ground ourselves in, there’s no connection, which depersonalizes us from our surroundings. With the rise of the internet and social media and the decline of identity when one steps back into the real world, it's little wonder our society has slipped into a crisis of loneliness. We are rudderless.

Out-of-town developers don’t face the consequences of their commodification. They don’t have to interact with the boxes they build on their way to work, going out to eat, or picking their kids up from school. They’re not a part of the community, so a Chipotle is just as good as Brian’s Burritos. At least I know Chipotle will pay rent on time, they do at my 10 other locations, the thought process goes. The prioritization of return over impact is one that may reflect kindly on P&L statements and investor update notices, but those extra basis points of IRR cripple local communities.

Don’t mistake this as a call for large developers to be prohibited from building. They provide a valuable service, especially in a time when we have such a dire need for new housing. But a system that makes it impossible for smaller builders to get their start is one that guarantees little will be built that is imbued with the pride and meaning of a specific contextual tradition. The only way to achieve this is through the cooperation of varied and diverse people working together to realize such a place together, reflecting their common mission in creating better places by the people, for the people.

Our places have become placeless. In order to reverse this trend, we must return to building in the ways we used to, which resulted in the types of places we revere so much today. We must allow for smaller lot development of fewer than 10 units by legalizing multi-family zoning in current single-family zones and prohibit the combination of lots to create larger buildings. We must encourage (and subsidize, where necessary) smaller builders and small businesses who want to have a hand in forming their own communities, but may have not had the resources or know how to do so. We must limit the impact from large capital aggregators in creating soul-crushing, corporatized environments that serve to commodify our places. If we don’t, they’ll never stop until everything looks like everything else, resembling nothing in particular at all.

We’re drawn to the great idiosyncrasies we find in places that imbue themselves with the collective identities of all of their people. In the name of self-determination, we have an obligation to lean into our places and allow for that bit of specialness that makes us so very fond of the best of them. Shame on us if we deprive our descendants of the many glories we’ve inherited in the built world in the name of 100 basis points of return.